Ardea herodias

(Great Blue Heron)

Description

The great blue heron is our largest heron standing at around four feet in height with a wing span of almost six feet. It is the largest heron in North America.

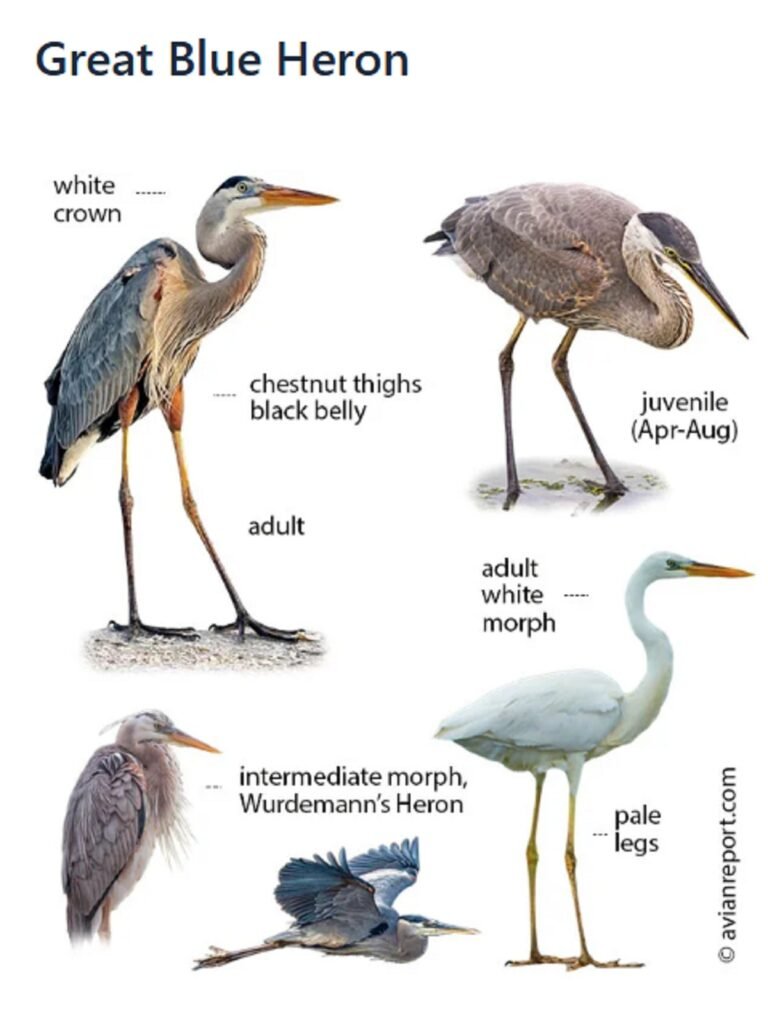

As adults they are gray-blue in color with a yellowish, long pointed, bill with both sexes looking alike.

Adults have a white face with black eye stripe that extends past their head in a plume of fine black feathers.

The necks of the adults are a grayish brown with a white stripe running down the middle front. The edges of this stripe have a thin border of black feathers giving it a black outline. Their breast is gray with some white mixed in and these feathers produce a beautiful feather plum that drapes down the front of their bodies.

Their bodies, and wings, are grayish blue with rust colored upper legs or thighs.

Juveniles, and non-breeding adults, lack the black head plume feathers. Juveniles also have streaked necks and breasts, a black head cap, and are a duskier gray overall.

“Maximum Recorded Lifespan for a great blue heron is 23 years and 3 months.” [1]

There is a morph of the great blue heron that is called the Wurdemann’s heron (Ardea herodias wardi x occidentalis) that can be entirely white, or a mixture of white and great blue heron colors, and is found only in marine habitats from the southern coast of South Carolina, south throughout Florida’s coast, to Cuba, Guatemala and Venezuela. The entirely white morph used to be classified as a great white heron but that has changed and it is no longer in the nomenclature. However, there is still much debate as to whether it is a distinct species and many want it re-classified as a great white heron. The totally white morph looks very similar to a great egret however; the great egret lacks any gray colorations, black head plumes, has black legs, and is about 10 to 12 inches shorter than either the great blue heron or the white morph. The great blue heron, and its morphs, do interbreed so some of these documented birds could just be a combination of genetics. Some scientists believe the all-white great blue heron should be classified as the great white heron as it once was.

“The Great White Heron was considered a separate species for nearly 140 years from the time of its original description (1835) by John James Audubon as Ardea occidentalis until 1973 when it was synonymized with the Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) by the American Ornithologists’ Union Committee on Classification and Nomenclature. Recent studies and syntheses have supported its re-elevation to full species status, a finding accepted by international authorities. In 2020, American Ornithological Society’s North American Classification Committee declined to accept a change in status….” extracted from an article in the Heron Biology and Conservation Journal found at HeronConservation.org titled The Great White Heron is a Species Volume 7, Article 1 (2022)

Common Names, Latin Name, and Family

Behavior

Great blue herons hunt with an incredible amount of camouflage for such a large bird. They move slowly through their territory and stay as still as a statue when hunting or avoiding being seen. If disturbed they usually take flight right away.

When great blue herons fly they fold their necks in unlike sandhill cranes which keep their necks extended out straight.

Their voice is a loud, harsh, squawk. They hunt both during the day and at night.

If you flush one from its nighttime hunting site it will let out a loud squawk and take flight. Many times they will fly about twenty feet ahead and hope you leave. I’ve had one do this four times, while I was taking a night walk along the canal, and on the fifth time it finally gave up and left the area completely.

Habitat

The great blue heron is common around most waterways, both fresh and saltwater, in Florida.

They hunt in the brush and undergrowth around lakes, rivers, ponds, marshes, canals, shorelines, mangroves, tide flats, and swamps. They are usually found at the edge of the water but will also stand in the water looking for food.

They can also be found hunting in wet meadows and floodplains.

Range

The great blue heron’s range is Florida and the southeastern United States and are year-round residents.

They are found as far north as Alaska, and as far south as Mexico and the West Indies. They are even found breeding in the Galapagos Islands.

Food

The great blue heron is an opportunistic feeder and will eat just about anything. Some people like to tame them with human food hand-outs but that’s not a good idea because they become habituated to humans (and the next person might not be kind) and human food can make them ill.

Their natural diet consists of just about anything they can catch and swallow. They prefer fish and frogs, but will eat reptiles, amphibians, birds, small mammals, and even other herons.

Nesting & Young

The great blue heron nests in colonies of other individuals as well as other water bird species.

The nest is made of sticks and brush to make a large platform with both male and female contributing to the building of it. A nest may be re-used from the previous year simply by tidying it up and adding a soft layer of green pine needles or other soft plant material available.

The nests are usually built higher than other water birds at around 30 to 70 feet up.

3 to 5, light blueish-green, eggs are laid. They are roughly 2 1/2 inches in size.

The eggs hatch at around 28 days and when the young emerge they are tended to by both parents. They are fed mostly fish.

Great blue heron chicks are semi-altricial which means the young hatch they are covered with down, not capable of leaving the nest, fed by their parents, and hatch with their eyes open.

There is a behavior amongst birds called piracy where one bird will steal another’s meal. In the case of the great blue heron … “Turkey vultures are known to force nestling Great Blue Herons to regurgitate their last meal, which is scooped up and later fed to the vultures’ own chick.” [2]

The young fledge, or leave the nest, at about 55 to 60 days.

Great blue herons are monogamous water birds.

For reference:

Semi-altricial chicks are covered with down, not capable of leaving the nest, fed by their parents, and hatch with their eyes open.

Altricial chicks do not have down when they hatch, are immobile, aren’t able to leave the nest to get food, and commonly (though not always) they have closed eyes.

Precocial birds such as ducks and chickens hatch with downy feathers, open eyes and are able to leave the nest and feed themselves within several hours (once their down dries).

Conservation

Although they are not a listed species there are still threats against their survival such as habitat loss, pesticide use, herbicide use, and human interference, particularly in areas of breeding birds.

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) protects the great blue heron in Florida, along with nearly all of our native birds. This federal law makes it illegal to hunt, capture, kill, or possess migratory birds, including their eggs and nests, without proper permits.

They are also protected by the animal cruelty statutes of Florida but good luck getting either of these laws enforced.

We are rapidly losing Florida species of animals and plants and I believe things need to change. Hopefully the future will be brighter and more enlightened people will be put in charge of our natural resources.

A Great Book for Florida Birders

If you love birding in Florida then you should add this book to your library because it gives you exact locations, and the best time of year, for finding Florida birds all throughout the state. You can’t go wrong with Bill Pranty’s advice because he knows where to find the birds you are looking for!

A Birder’s Guide to Florida by Bill Pranty

Footnotes

Footnotes

[1] Page 645, Lifespan Chart

[2] “Piracy” Page 159, Paragraph 3