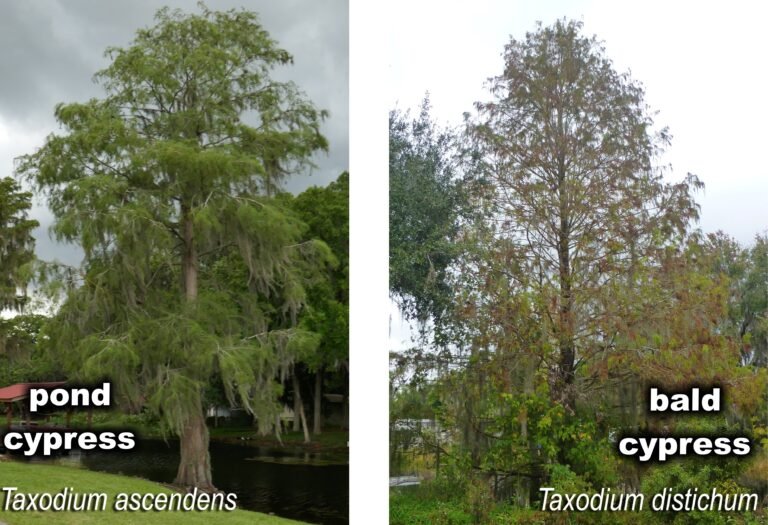

Pond Cypress and Bald Cypress Trees

Some botanists claim that these should be classified as the same tree, however, there are quite a few distinct characteristics in each species which make each of them very different from the other.

Both can be used in the home landscape in average to moist soils, and standing water. Even though they are considered wetland trees, they will thrive in drier environments, and in those drier places they don’t produce as many “knees” as they do growing in water. Most botanists believe the knees are reaching out of the water to get air when the roots are submerged by water. Knees tend to be bent and buckled roots as they grow out of the water.

Both are very large trees so that has to be taken into consideration when planting them in your green space. Avoid planting them near septic systems, home foundations, or sea walls because they do have aggressive root systems. Not to mention the fact that the knees create a maintenance nightmare if they come up in a walking path or a place you regularly mow because they can break a mower or blade, and they become a trip hazard in a walking path.

Cypress domes are a regular sight in Florida. You may be familiar with cypress domes if you’ve been to Florida coastal areas. Usually scattered throughout the miles of sawgrass are domes of vegetation dominated by cypress trees. Both species of cypress tree can sometimes be found. These ecosystems appear dome shaped because the taller, more mature, trees grow in the center and the younger, shorter trees, grow around the perimeter.

“Considering their relatively small size, the biodiversity and complexity in cypress domes is remarkable. Over 300 plant species have been identified in and around cypress domes, including ferns, sedges, grasses, shrubs, and wildflowers that thrive in wet, acidic soils. … Cypress domes provide habitat for more than 120 bird species, including barred owl, ibis, heron, wood duck, and many migratory songbirds. The dense canopy, cool shade underneath, and standing water offer ideal conditions for nesting, feeding, and shelter. … More than 100 invertebrate species such as aquatic insects, crustaceans, and mollusks are also found in the water and soil of cypress domes. The ecosystem also supports a wide range of amphibians and reptiles, including southern leopard frogs, tree frogs, turtles, cottonmouth snakes, and American alligators. 40 mammal species are known to utilize cypress domes. These include raccoons, river otters, bobcats, marsh rabbits, and white-tailed deer, many of which rely on the domes for foraging and cover. [1]

It is well worth the effort to fight through the sawgrass to get to a cypress dome. Once you reach it, you will be rewarded with a shaded wonderland of plants and animals. They truly are magical spots in the Florida landscape.

In Florida we have two cypress trees … the pond cypress and the bald cypress. Both can be found in cypress domes but usually the dominant tree is the bald cypress. Below you can read about the two and learn the identifying features of each.

Pond Cypress

Latin Name: Taxodium ascendens

Common Names: both species may be called by the same common names such as swamp cypress and southern cypress, however this one is generally called pond cypress.

Family: pond cypress is found in the Cupressaceae, or cedar, family. Taxodium ascendens (pond cypress) and Taxodium distichum (bald cypress) are the only Taxodiums in this family.

Form: pond cypress is a medium to large deciduous tree that grows to a height of about 80 feet but has the potential to reach up to 130 feet in height.

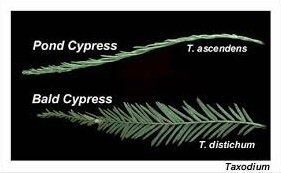

Leaves: pond cypress leaves are appressed, or flat, against the stems and are imbricate, meaning they overlap each other.

Flowers: The male and female flowers grow on the same tree, which means that cypress trees are monoecious. The male flowers appear as long droops of tassels of tiny pollen filled cones. The female cones form large round balls in which the fruit/seeds form once pollinated and when mature, with viable seeds, they are about an inch across and turn a deep brown color. The male flowers shed their pollen about 3-4 weeks later than bald cypress.

Knees: pond cypress has shorter knees with more mounded shapes than the bald cypress. Pond cypress knees are usually only about 1 foot in height and the summit, or tip, of the knee usually has thick bark growing on it.

Habitat: pond cypress is found naturally occurring in pine flatwood pond margins, wet sandy depressions, lakes, canals, and other riparian areas.

Native Range: pond cypress is found in the southeastern United States from Virginia south to Florida, and west to Texas. It is found in quite a few counties in Florida, but is not as prolific as the bald cypress.

Landscape Use: in the home landscape, pond cypress grows fastest in full sun with moist to wet soils. It isn’t a good candidate for areas where people walk because of the cypress knees that develop from the roots of this tree. The knees create a trip hazard. Much of the literature states that the knees don’t develop when the tree is grown in a dry location. It is definitely not a tree to grow near your septic system, or home foundation, because the roots extend out to a large area and when the knees grow they can dislodge foundations and destroy septic systems.

Wildlife Uses: Many of our native wildlife eat cypress seeds including wild turkey, wood ducks, songbirds, squirrels, waterfowl and wading birds. Cypress domes provide unique watering places for a variety of birds and mammals and breeding sites for frogs, toads, salamanders and other reptiles.

Propagation: pond cypress can be grown from seed or transplanting individual specimens. When transplanting, try to keep as much soil with the roots as you can, and it will have a better chance of surviving the move. Many times very small seedlings can be found at the base of mature trees and if these are gently put into growing pots, with little root disturbance, the success rate for survival is fairly good. As with larger specimens, try to retain as much soil around the seedling’s roots as possible.

Bald Cypress

Latin Name: Taxodium distichum

Common Names: bald cypress, swamp cypress, red cypress, southern cypress, and white cypress.

Family: bald cypress is found in the Cupressaceae, or cedar, family. Taxodium ascendens (pond cypress) and Taxodium distichum (bald cypress) are the only Taxodiums in this family.

Form: bald cypress is a deciduous tree that grows to a height of 130 feet. The base of the trunk becomes buttressed with age, and its roots create above ground “knees”. [2] Young trees are more pyramid shaped and symmetrical, whereas older trees become unsymmetrical and jagged looking.

Leaves: the needle like leaflets of bald cypress are alternate on the stem. Individual leaflets are 1/2 to 3/4 an inch in length, and have a feathery appearance. In the fall, the foliage turns a reddish brown as the leaves are falling off the tree.

Flowers: The male and female flowers grow on the same tree, which means that cypress trees are monoecious. The male flowers appear as long droopy tassels of tiny pollen filled cones. The female cones form large round balls in which the fruit/seeds form once pollinated. The flowers are wind pollinated. The male cones shed their pollen about 3-4 weeks earlier than those of the pond cypress. When the female cones become filled with mature seeds, they are about an inch across. The seeds come apart in large flakes within the cone. Wait until it turns brown and break it apart to separate the viable seeds. Be aware that the cones emit a sticky sap so it is best to clean the seeds with gloves on.

Knees: bald cypress knees grow much taller than pond cypress knees. Bald cypress knees can get up to 6 feet tall. The bark at the summit, or tip, is usually very thin. The shape is irregular, with most being conical.

Habitat: bald cypress prefers moving water and is found naturally occurring in lake margins, swamps, floodplains, streams, sloughs, the backwater of coastal marshes, and other riparian areas.

Native Range: bald cypress is found naturally occurring in the southeastern United States. It is found in every Florida county except for St. Lucie county and the Keys.

Landscape Use: in the home landscape bald cypress grows fastest in full sun with moist to wet soils. It isn’t a good candidate for areas where people walk because of the cypress knees that develop from the roots of this tree. The knees create a trip hazard. Although much literature states, the knees don’t develop when the tree is grown in a drier soil. It is definitely not a tree to grow near your septic system, or home foundation, because the roots extend out to a large area and when the knees grow they can dislodge foundations and destroy septic systems.

Wildlife Uses: Many of our native wildlife eat cypress seeds including wild turkey, wood ducks, songbirds, squirrels, waterfowl and wading birds. Cypress domes provide unique watering places for a variety of birds and mammals and breeding sites for frogs, toads, salamanders and other reptiles. The knees provide cover from predators for smaller animals and many times gives them a chance to escape predation from larger hunters.

Propagation: bald cypress can be grown from seed or transplanting individual specimens. When transplanting, try to keep as much soil with the roots as you can, and it will have a better chance of surviving the move. Many times very small seedlings can be found at the base of mature trees and if these are gently put into growing pots, with little root disturbance, the success rate for survival is fairly good. As with larger specimens, try to retain as much soil around the seedling’s roots as possible.

Champion Cypress Trees

The National Champion Pond Cypress (Taxodium ascendens) is in Lake County, Florida. As of 2020 there were two co-champions measuring 16.5 to 20.4 feet in circumference, heights of 95 and 135 feet feet, and crown spreads of 73.5 and 80.5.

The National Champion Bald Cypress (Taxodium distichum) is in West Feliciana county, Louisiana. The trunk circumference is 52 ft, height is 91 feet, crown spread is 87 feet as of 2017. It is not publicly accessible.

Footnote

[1] Ecosystem Explorer- Cypress Domes

[2] Godfrey, Robert K.. Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines of Northern Florida and Adjacent Georgia and Alabama. Univ. of Georgia Press. 1988